What is Nature Based Learning?

- celesteanndesigns

- Oct 1, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 4, 2022

Nature Based Learning (NBL), a term sometimes used interchangeably with Nature Pedagogy (Miller et al., 2020), refers not necessarily to learning about nature, but to using nature as a tool for learning (Miller et al., 2020).

Learner Perspective: ‘This is a transportation place. We put water and if you want to go to another place, you should put your hand inside of it’ (Kandemir & Sevimli-Celik, 2021, p. 9).

Note. Loose parts pretend play transporation circle (Kandemir & Sevimli-Celik, 2021) p. 9

Learners engaging in NBL may be acquiring new knowledge, skills, or values about any topic (Jordon & Chawla, 2019). The defining feature is that the topic is learned using nature, whether structured or unstructured, alone or in a group, guided or self-directed, formal, informal or non-formal. Warden (2019) states that nature pedagogy has a deeper meaning than using natural elements as tools or being outdoors, explaining that it is about always placing the natural world at the center of what you are doing. Warden's article about Nature Pedagogy has limited references to other literature and many uses of emotive language, so cannot be relied on for accuracy. However, it offers an interesting perspective on nature pedagogy and some practical examples of ways to include it in curriculum.

Because it often occurs outdoors in nature, NBL at times inherently overlaps with pedagogies such as Place-Based Learning, Risky Play and Forest Kindergarten or Outdoor Classrooms. Forest Kindergartens, often known as Bush Kinder or Beach Kinder in Australia (Campbell & Speldewinde, 2019) are set outdoors in the natural environment, where children engage in learning through play with natural elements (Fjørtoft, 2001; Coe, 2016) and encounters with experiential phenomenon such as weather and changes in the landscape (Campbell & Speldewinde, 2019). For this reason, Forest Kindergartens fall under the definition of NBL. Campbell and Speldewinde (2019), explain that in Forest Kindergartens there is a link with place-based learning because the local environment’s natural characteristics and wildlife change how children can interact with it. “Each site facilitates children a connection with, and contribution to, the natural environments in the child’s world” (p. 556). Risky play is inherent to some degree in outdoor play due to the affordances of the natural environment (Little and Sweller, 2015). The natural environment allows children to take risk assessments with the help of teachers and then practise risk management (Elliot & Chancellor, 2014). Therefore, when NBL is implemented in an outdoor setting, there are elements of risky play involved. Loose parts learning is another pedagogy that overlaps with NBL. When natural elements are used for learning in an unstructured way (remembering that this is only sometimes the case in NBL), the elements do not have a predetermined use, so they can be open-ended loose parts (Miller et al., 2020).

Examples of Nature Based Learning in Practise

Below are examples of Nature Based Learning.

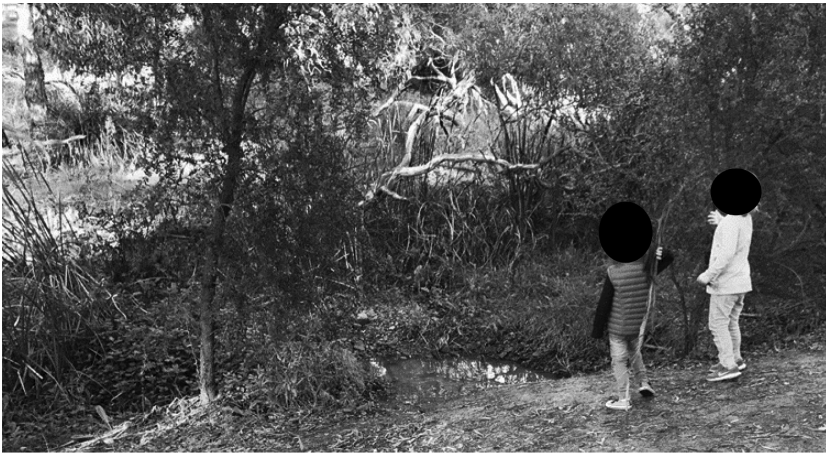

Speldewinde & Campbell (2021) examined how Bush Kinder can enable girls’ STEM identities in early childhood. Below is a photograph of two students using natural objects and a creek to hypothesise and experiment, testing whether objects float or sink in the water.

Note. Two girls at Bush Kinder testing sinking and floating (Speldewinde & Campbell, 2021). P. 9.

Streelasky (2019) examined children’s creation of multi-model texts and development of literacy in a forest kindergarten setting. One child included in the research, Dustin, took the photograph below along with many others as his text – his expression of what he valued in his learning.

Dustin's narrative accompanying his photography: "I like playing in the fallen logs and trees on the play-ground; it is so much fun, but a bit scary too! I like the big pile of sticks and logs that we made–it is for another fort that is going to be really high off the ground." (P. 99)

Note. Photographical text by a child in a Forest Kinder showing the sticks his friends are gathering for a fort (Streelasky, 2019). P. 99.

References

Jordan, C. & Chawla, L. (2019). A Coordinated Research Agenda for Nature-Based Learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(766). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00766

Kandemir, M. & Sevimli-Celik, S. (2021). Pretend Play ‘Transportation Circle' [Photograph]. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2021.2011339

Miller, N., Kumar, S. & Pearce, K. (2020). The outcomes of nature-based learning for primary school aged children: a systematic review of quantitative research. Environmental Education Research, 27(8), 1115–1140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1921117

Speldewinde, C. & Campbell, C. (2021). Bush kinders: enabling girls’ STEM identities in early childhood. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2021.2011337

Speldewinde, C. & Campbell, C. (2021). Testing Floating and Sinking [Photograph]. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2021.2011337

Streelasky, J. (2019). A forest-based environment as a site of literacy and meaning making for kindergarten children. Literacy, 53(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12155

Streelasky, J. (2019). Dustin’s text of his active and collaborative play with his peers in the forest. [Photograph]. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2021.2011337

Warden, C. (2019). Nature Pedagogy: Education for sustainability. Childhood Education, 95(6), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2019.1689050

Comments